| ||||

My Vietnam Nightmare

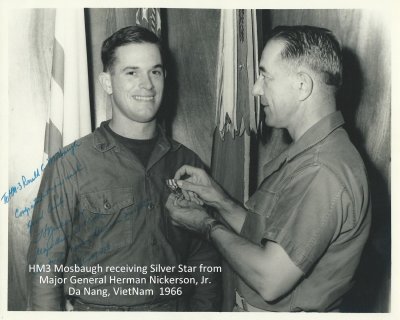

By Corpsman Ronald C. Mosbaugh

2/1 Hotel Company 1966-1967

HMCM USNR RET.

Email: RMosbaugh@outlook.com

When I landed in Vietnam in 1966, I was an immature twenty-year-old country boy who was naïve about the ways of the world. Coming into a war zone, I was so innocent and naïve. It was a culture shock beyond description. Everything I held sacred was shattered; life was turned upside down and my innocence was violently raped and ripped away. In Vietnam, we saw and experienced things that we could never conceive of and could never truly communicate to someone who wasn’t there.

For the past forty-eight years, I have suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) due to my tour in Vietnam. One of the most common symptoms of PTSD is Post Traumatic Nightmares (PTNMs). Like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day, I keep having the same dream over and over. After a while I question myself over what is real and what is imaginary. It is hard for my mind to differentiate between the two.

Our platoons leapfrog from one cemetery to another. The final graveyard we enter is a little less than two acres with one hundred graves. As we pass through the perimeter, the Vietcong spring their trap, as each VC is lying on a tomb. The heights of all the graves are above eye level, with tall grass growing on top of them. They’re approximately six to eight feet across in diameter. The VC open fire on us at a point blank distance. It’s a well-executed trap.

During my entire tour of thirteen months on the front line, I’ve never encountered guerilla warfare of this magnitude. The Vietcong want a great victory. A call is made by the radio operator, Corporal Gerace, aka “Bomar,” that the first platoon needs a corpsman. I run as quickly as I can to give the Marines medical care. As I’m running across the rice paddy, which is about 75 yards towards the battle, I hear bullets whizzing by me. I’m trying to keep my body as low to the ground as possible. One of the bullets comes so close to my ear that if it was any closer, my name would have been written on the Vietnam Wall. It’s the most horrifying and frightening sound I have ever heard in my life. During my marathon run, other bullets splash in the rice paddy water next to me.

As I’m running toward the battle, my adrenaline is racing extremely fast and the suction from the mud is wearing me out. It seems I’m running in slow motion. When I get to the first grave, I collapse with exhaustion, gasping for air. Terrified, I think this could very likely be the last day of my life. This suicidal waltz is known as “doing your duty.”

The sound of weapons firing and grenades exploding is deafening. The only battle where we encountered hand-to-hand combat during my tour in Vietnam, this battle gets personal and up close, a fight to the death. It is a life changer that crushes all I perceive of what life is about. I can hear Marines yelling from being wounded and in pain. As I go around the graves looking for wounded, what I see is overwhelming. There are bodies everywhere, Marines and Vietcong. I am confused and in a panic. Who am I going to treat first? Where’s the other Corpsman? I scream in my head, I need help! I also need to watch for the Vietcong. I try to use triage as much as possible; but with so many Marines needing medical care, I just have to do the best I

can. I’m not prepared for as many causalities as we endure. Consequently, I run out of battle dressings. Some of the Marines carry them in their pockets, so I always check their pants first. I also run out of morphine, which causes more agony for the maimed.

Chaos is everywhere. We are all fighting for our lives. I am constantly looking for wounded Marines and watching for the enemy, they too are everywhere. While I’m treating a Marine for a gut wound, I look up and see a Vietcong looking at me. He is about twenty feet from me with a rifle in his hand. The shock is so great that the boy I was dies of fright. At this moment the world around me seems to be suspended in time. The noise of the battle ceases and everything is at a standstill. I am in a twilight zone where it is hard for me to digest the events taking place.

The Vietcong is holding his rifle in one hand, the barrel pointing slightly downward. My hands are busy treating the Marine. My 45 caliber pistol is in my holster, and my rifle is lying on the ground next to me. I have no doubt that the VC is contemplating on whether to kill me or move on. He’s about my age with black shorts, black shirt, and sandals. His hair is dark black, thick, and unkempt. The dark eyes stare at me with a haunting glaze. It’s as if he is looking through me.

During my previous time in Vietnam, I was scared but not to the extent at this moment. My life is at his discretion. All he has to do is tilt the rifle up and fire. So many things are going through my mind. Was this the last day of my life? Will I ever see my family again? What will happen to the Marine I am treating and the rest of our casualties? These are all split second thoughts.

Suddenly, a thought occurs to me that perhaps he is not going to kill me. I start to feel calmness. I no longer feel fear. I start to look at him as a warrior who is doing what his superiors trained him to do. He does have a conscience and he is contemplating what is right and what is wrong. He can see that I am treating a fellow Marine. Would he not do the same thing for one of his comrades? I start to feel compassion for him and at that moment I want him to live. I start to yell at him telling him I am a” bac si” (doctor). I tell him “didimau” (go quickly). My Vietnamese is very limited, but I get the point across. I know if a Marine sees him, he will kill him instantly.

The Marine I am treating is in much pain. I look down at him and he is in shock and bleeding out. During my dream, I look back at the Vietcong and he is gone. At this instant the chaos of the war returns, and we are no longer suspended in time.

This nightmare has haunted me for over forty-eight years. We started with 90 Marines and only 26 of us walked out that day. I was awarded the Silver Star for this operation.

I have dreamed this nightmare over and over. Each time I dream it, it reinforces my belief about what I think happened. Whether it is right or not, it is the way I perceived it.

HMCM Ronald Mosbaugh

USNR Retired